Here’s a typical story:Â Frank, a 7-year-old boy, often “blanks out” anywhere from a few seconds to 20 seconds at a time. During a seizure, Frank doesn’t seem to hear his teacher call his name, he usually blinks repetitively, and his eyes may roll up a bit. During shorter seizures, he just stares. Then he continues on as if nothing happened. Some days Frank has more than 50 of these spells.

How long do they last?

Usually less than 10 seconds, but it can be as long as 20. They begin and end suddenly.

Tell me more

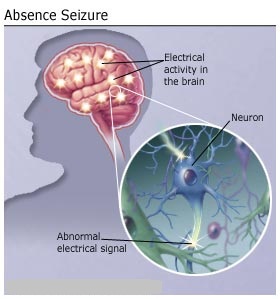

Absence seizures are brief episodes of staring. (Although the name looks like a regular English word, your neurologist may pronounce it ab-SAWNTZ.) Another name for them is petit mal (PET-ee mahl). During the seizure, awareness and responsiveness are impaired. People who have them usually don’t realize when they’ve had one. There is no warning before a seizure, and the person is completely alert immediately afterward.

Absence seizures are a type of generalized seizures. They were first described by Poupart in 1705, and later by Tissot in 1770, who used the term petit access. In 1824, Calmeil used the term absence. In 1935, Gibbs, Davis, and Lennox described the association of impaired consciousness and 3-Hz spike-and-slow-wave complexes on electroencephalograms (EEGs).

Absence seizures occur in idiopathic and symptomatic generalized epilepsies. Among the idiopathic generalized epilepsies, absence seizures are seen in childhood absence epilepsy (pyknolepsy), juvenile absence epilepsy, and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (impulsive petit mal). The seizures in these conditions are called typical absence seizures and are usually associated with generalized 3-4 Hz spike-and-slow-wave complexes on EEG.

In childhood absence epilepsy, seizures are frequent and brief, lasting just a few seconds (pyknoleptic). Some children can have many such seizures per day. In other epilepsies, particularly those with an older age of onset, the seizures can last several seconds to minutes and may occur only a few times a day; these are called nonpyknoleptic or spanioleptic absence seizures.

Myoclonic and tonic-clonic seizures may also be present, especially in syndromes with an older age of onset.

In the cryptogenic or symptomatic generalized epilepsies, absence seizures are often associated with slow spike-wave complexes of 1.5-2.5 Hz; these are also called sharp-and-slow-wave complexes. These seizures may be associated with loss of axial tone and head nodding; a fall may occur. Increased tone, autonomic features, and automatisms may also be seen. Absence seizures associated with slow spike-wave complexes are called atypical absence seizures.

Simple absence seizures are just stares. Many absence seizures are considered complex absence seizures, which means that they include a change in muscle activity. The most common movements are eye blinks. Other movements include slight tasting movements of the mouth, hand movements such as rubbing the fingers together, and contraction or relaxation of the muscles. Complex absence seizures are often more than 10 seconds long.

Who gets them?

Absence seizures usually begin between ages 4 and 14. The children who get them usually have normal development and intelligence.

What’s the outlook?

In nearly 70% of cases, absence seizures stop by age 18. Children who develop absence seizures before age 9 are much more likely to outgrow them than children whose absence seizures start after age 10.

Children with absence seizures do have higher rates of behavioral, educational, and social problems.

What else could it be?

Absence seizures can resemble some complex partial seizures or episodes of daydreaming:

Questions to Ask |

Daydreaming |

Seizures |

| How frequent are the episodes? | Not frequent. | Complex partial:Â Rarely more than several times per day or week. Absence:Â Could be many times per day. |

| In what situations do they occur? | Boring situation. | Any time, including during physical activity; often with hyperventilation (deep or rapid breathing.) |

| Do they begin abruptly? | No. | Usually yes. Some complex partial seizures begin slowly with a warning. |

| Can they be interrupted? | Yes. | No. |

| How long do they last? | Until something interesting happens. | Complex partial:Â Up to several minutes Absence:Â Rarely more than 15-20 seconds |

| Does the person do anything during the episode? | Probably just stares. | Complex partial:Â Automatisms are common. Absence:Â Just stares. |

| What is the person like immediately after the episode? | Alert. | Complex partial:Â Confused. Absence:Â Alert. |

How is the diagnosis made?

The EEG (electroencephalogram), which records brain waves, is helpful in diagnosing absence seizures. Having the child breathe very rapidly often will produce a seizure. Images of the brain such as CT and MRI scans are usually normal, so they are seldom needed if the EEG and other features are typical.

Neuroimaging Studies

Neuroimaging findings are normal in idiopathic epilepsies by definition, and therefore, neuroimaging is not indicated if the typical clinical pattern is present.

However, neuroimaging is often ordered by primary care providers and the emergency department, especially if a child presents with a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, to rule out significant structural causes of seizures. A normal result helps to support the diagnosis of idiopathic epilepsy. For cryptogenic and symptomatic generalized epilepsies, neuroimaging can help in the diagnosis of any underlying structural abnormality.

If imaging is performed, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred to computed tomography (CT) scanning. MRI is more sensitive for certain anatomic abnormalities.

A review of 134 MRI scans in patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsies found nonspecific abnormalities in 24%.