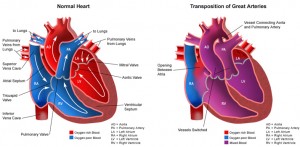

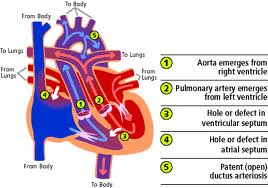

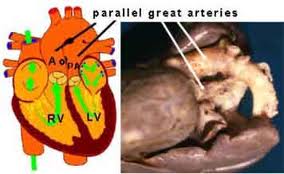

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) is the most common cyanotic congenital heart lesion that presents in neonates. The hallmark of transposition of the great arteries is ventriculoarterial discordance, in which the aorta arises from the morphologic right ventricle and the pulmonary artery arises from the morphologic left ventricle.

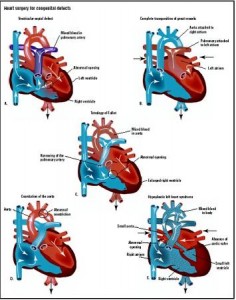

Although transposition of the great arteries was first described over 2 centuries ago, no treatment was available until the middle of the 20th century, with the development of surgical atrial septectomy in the 1950s and balloon atrial septostomy in the 1960s. These palliative therapies were followed by physiological procedures (atrial switch operation) and anatomic repair (arterial switch operation). Today, the survival rate for infants with transposition of the great arteries is greater than 90%.

Although transposition of the great arteries was first described over 2 centuries ago, no treatment was available until the middle of the 20th century, with the development of surgical atrial septectomy in the 1950s and balloon atrial septostomy in the 1960s. These palliative therapies were followed by physiological procedures (atrial switch operation) and anatomic repair (arterial switch operation). Today, the survival rate for infants with transposition of the great arteries is greater than 90%.

The major anatomic classifications of transposition of the great arteries depend on the relationship of the great arteries to each other and/or the infundibular morphology. In approximately 60% of the patients, the aorta is anterior and to the right of the pulmonary artery (dextro-transposition of the great arteries [d-TGA]). However in a subset of patients, the aorta may be anterior and to the left of the pulmonary artery (levo-transposition of the great arteries [l-TGA]). In addition, most patients with transposition of the great arteries (regardless of the spacial orientation of the great arteries) have a subaortic infundibulum, an absence of subpulmonary infundibulum, and fibrous continuity between the mitral valve and the pulmonary valve. Despite these useful classifications, several exceptions are noted, and, hence, discordant ventriculoarterial connection is the only distinguishing characteristic that defines transposition of the great arteries.

From a practical standpoint, the presence or absence of associated cardiac anomalies defines the clinical presentation and surgical management of a patient with transposition of the great arteries. The primary anatomic subtypes are:

From a practical standpoint, the presence or absence of associated cardiac anomalies defines the clinical presentation and surgical management of a patient with transposition of the great arteries. The primary anatomic subtypes are:

(1) transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum,

(2) transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect,

(3) transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and

(4) transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect and pulmonary vascular obstructive disease.

In approximately one third of patients with transposition of the great arteries, the coronary artery anatomy is abnormal, with a left circumflex coronary arising from the right coronary artery (22%), a single right coronary artery (9.5%), a single left coronary artery (3%), or inverted origin of the coronary arteries (3%) representing the most common variants.

Pathophysiology

The pulmonary and systemic circulations function in parallel, rather than in series. Oxygenated pulmonary venous blood returns to the left atrium and left ventricle but is recirculated to the pulmonary vascular bed via the abnormal pulmonary arterial connection to the left ventricle. Deoxygenated systemic venous blood returns to the right atrium and right ventricle where it is subsequently pumped to the systemic circulation, effectively bypassing the lungs. This parallel circulatory arrangement results in a deficient oxygen supply to the tissues and an excessive right and left ventricular workload. It is incompatible with prolonged survival unless mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood occurs at some anatomic level.

The pulmonary and systemic circulations function in parallel, rather than in series. Oxygenated pulmonary venous blood returns to the left atrium and left ventricle but is recirculated to the pulmonary vascular bed via the abnormal pulmonary arterial connection to the left ventricle. Deoxygenated systemic venous blood returns to the right atrium and right ventricle where it is subsequently pumped to the systemic circulation, effectively bypassing the lungs. This parallel circulatory arrangement results in a deficient oxygen supply to the tissues and an excessive right and left ventricular workload. It is incompatible with prolonged survival unless mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood occurs at some anatomic level.

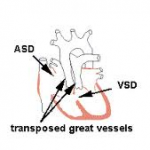

The following are 3 common anatomic sites for mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in transposition of the great arteries:

- Atrial  septal defect

- Ventricular septal defect

- Patent  ductus arteriosus

One or all of these lesions can be present in concert with dextro-transposition of the great arteries, and the degree of arterial hypoxemia depends on the degree of anatomic mixing.

Epidemiology

Frequency

United States

Despite its overall low prevalence, transposition of the great arteries is the most common etiology for cyanotic congenital heart disease in the newborn.This lesion presents in 5-7% of all patients with congenital heart disease. The overall annual incidence is 20-30 per 100,000 live births, and inheritance is multifactorial. Transposition of the great arteries is isolated in 90% of patients and is rarely associated with syndromes or extracardiac malformations. This congenital heart defect is more common in infants of diabetic mothers.

Despite its overall low prevalence, transposition of the great arteries is the most common etiology for cyanotic congenital heart disease in the newborn.This lesion presents in 5-7% of all patients with congenital heart disease. The overall annual incidence is 20-30 per 100,000 live births, and inheritance is multifactorial. Transposition of the great arteries is isolated in 90% of patients and is rarely associated with syndromes or extracardiac malformations. This congenital heart defect is more common in infants of diabetic mothers.

Mortality/Morbidity

The mortality rate in untreated patients is approximately 30% in the first week, 50% in the first month, and 90% by the end of the first year. With improved diagnostic, medical, and surgical techniques, the overall short-term and midterm survival rate exceeds 90%.

Long-term complications are secondary to prolonged cyanosis and include polycythemia and hyperviscosity syndrome. These patients may develop headache, decreased exercise tolerance, and stroke. Thrombocytopenia is common in patients with cyanotic congenital heart disease leading to bleeding complications.

Patients with a large ventricular septal defect, a patent ductus arteriosus, or both may have an early predilection for congestive heart failure, as pulmonary vascular resistance falls with increasing age. Heart failure may be mitigated in those patients with left ventricular outflow tract (pulmonary) stenosis.

A small percentage (approximately 5%) of patients with transposition of the great arteries (and often a ventricular septal defect) develop accelerated pulmonary vascular obstructive disease and progressive cyanosis despite surgical repair or palliation. Long-term survival in this subgroup is particularly poor.

Race

No racial predilection is known.

No racial predilection is known.

Sex

TGA has a 60-70% male predominance.

Age

Patients with TGA usually present with cyanosis in the newborn period, but clinical manifestations and courses are influenced predominantly by the degree of intercirculatory mixing.

Clinical Features

Newborns with transposition of the great arteries are usually well developed, without dysmorphic features. Physical findings at presentation depend on the presence of associated lesions.

Newborns with transposition of the great arteries are usually well developed, without dysmorphic features. Physical findings at presentation depend on the presence of associated lesions.

- Transposition of the great arteries with intact ventricular septum: Infants typically present with progressive central (perioral and periorbital) cyanosis. Other than cyanosis, the physical examination is often unremarkable.

- Transposition of the great arteries with large ventricular septal defect: Cyanosis may be mild initially, although it is usually more apparent with stress or  crying. Upon presentation, infants often have an increased right ventricular impulse, a prominent grade 3-4/6 holosystolic murmur, third heart sound, mid-diastolic rumble, and a gallop rhythm. Hepatomegaly may be present.

- Transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: Cyanosis is prominent at birth, and the findings are similar to those of infants with tetralogy of Fallot. A single, or narrowly split, diminished second heart sound and a grade 2-3/6 systolic ejection murmur may be present. Hepatomegaly is rare.

- Transposition  of the great arteries with ventricular septal defect and pulmonary vascular obstructive disease: Progressive pulmonary vascular obstructive disease is not always evident from physical examination findings. Cyanosis is usually present and can progress despite palliative therapy in the newborn period.

- No murmur (despite the ventricular septal defect) or early short systolic ejection sounds are heard.

- The second heart sound is often single, with increased intensity.

- In later childhood or adolescence, a high-pitched, blowing, early decrescendo diastolic murmur of pulmonary insufficiency and a blowing apical murmur of mitral insufficiency are evident.