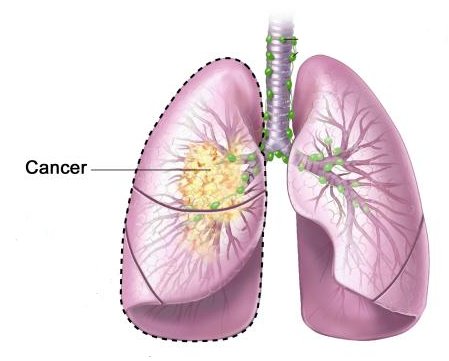

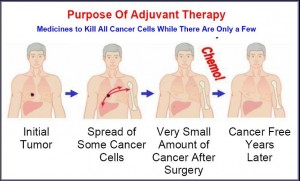

The use of chemotherapy after curative resection is standard in many common malignancies such as breast and colon cancer and is commonly described as adjuvant therapy. The magnitude of benefit with respect to improvement in disease-free and overall survival in many cases is often small in absolute terms especially in the case of breast cancer where absolute potential improvements may only be in the range of 5% at 10 years. Lung cancer is the most lethal of the common malignancies with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprising approximately 80% of cases. Unfortunately, only a minority of patients present with resectable disease, and despite this, the median survival with curative intent surgery is relatively poor (pathological stage I disease 67% at 5 years, pathological stage 2b disease 39% at 5 years). NSCLC is predominantly a disease of the elderly with median age at diagnosis of 68 years, and its management is often complicated by the relatively high rate of concomitant illnesses.

Chemotherapy for advanced disease has only been routinely accepted for the past 10 years since the publication of a meta-analysis in 1995. This demonstrated an improvement in overall survival compared with best supportive care using platinum-based chemotherapy. No statistically significant improvement was demonstrated in the adjuvant setting (n = 1394, HR 0.87, p = 0.07). Concern with regard to toxicity for a relatively small gain in survival slowed its widespread application in the palliative setting; however, subsequent studies utilising modern platinum-based doublets have shown an improvement in quality of life in addition to survival. The availability of active and well-tolerated chemotherapy regimens subsequently led to the investigation of its use in the adjuvant setting.

Chemotherapy for advanced disease has only been routinely accepted for the past 10 years since the publication of a meta-analysis in 1995. This demonstrated an improvement in overall survival compared with best supportive care using platinum-based chemotherapy. No statistically significant improvement was demonstrated in the adjuvant setting (n = 1394, HR 0.87, p = 0.07). Concern with regard to toxicity for a relatively small gain in survival slowed its widespread application in the palliative setting; however, subsequent studies utilising modern platinum-based doublets have shown an improvement in quality of life in addition to survival. The availability of active and well-tolerated chemotherapy regimens subsequently led to the investigation of its use in the adjuvant setting.

Researchers in the US have developed a gene test that could predict which patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) still have a low chance of surviving despite having their disease diagnosed early (stage 1). Adjuvant ‘therapy’ had been explored in NSCLC for the past two decades. The 1995 meta-analysis discussed above found no benefit for cisplatin-based chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting. Treatment for lung cancer – the second most common cancer in the UK after breast cancer – varies depending on how advanced the disease is when it is diagnosed.

About 12 per cent of people diagnosed with NSCLC are diagnosed with stage I cancer, which is defined as a cancer smaller than five cm that has not spread to any other part of the body.

For patients with stage I NSCLC, the routine treatment is surgery only, and this cures around two-thirds of patients.

While additional chemotherapy is an extra option for patients with later stages of the disease, it has not been shown to improve survival in early stage patients, and can cause considerable side effects, especially for older patients. Post-operative radiotherapy was reviewed in a meta-analysis by the Medical Research Council in 1998 and demonstrated that postoperative radiotherapy was deleterious to survival with only the stage III N2 group unaffected. This may be explained in part by older machines and inferior techniques to those routinely instituted today. Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation was compared with radiotherapy alone in one study by Keller et al. for patients with resected stage II or IIIA NSCLC. Four hundred and eighty-eight patients were enrolled. Four cycles of cisplatin-etoposide were administered with the first given in combination with radiotherapy. Sixty-nine percent of patients were able to receive all four planned chemotherapy cycles. Treatment mortality was 1.2 and 1.6%, respectively. No advantage for the combined approach was demonstrated for overall or progression-free survival.

Adjuvant chemotherapy has been compared with observation ± radiotherapy in eight recent studies reported since the publication of the 1995 meta-analysis. Three of which have been limited to stage I-II disease (early stage).

This study by Dr Michael J Mann and Professor David M Jablons, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Thoracic Surgery Division, measured the activity of 14 genes in tumour tissue taken from 361 patients diagnosed with stage I NCSLC.

The pattern of gene activity levels was then analysed, and compared to the patients’ outcomes. From this, the researchers were able to find genetic ‘fingerprints’ for people at high, medium and low risk of the cancer coming back.

To confirm these findings, the researchers then repeated the test on a further 433 stage I NCSLC patients from hospitals around California, and on 1,006 patients from hospitals around China, who were diagnosed with stage I, II or III disease.

The authors found that the test was the “strongest predictor” of patients’ fates compared with standard criteria such as age and smoking status. It also outperformed guidelines used to identify high-risk patients with early stage disease.

Professor Siow Ming Lee, Cancer Research UK’s lung cancer expert, said the findings were “encouraging”.

“If this finding is confirmed in larger studies, a test to detect this profile could be used to carry out new clinical trials to find out whether adjuvant chemotherapy would help treat such poor prognosis early stage patients.

But he cautioned that the test needed to be shown to work in much larger groups of patients, and that questiones remained over some aspects of the study.

“It isn’t clear whether the patients in the validation arms of the study had the stage of their tumour accurately measured by the current standard of care – PET-CT scanning and/or endobronchial ultrasound,” he added.

“It’s also possible that this gene profile is an indication of more aggressive disease, and that these patients would be unlikely to benefit from chemotherapy. To find out, it would be useful to look at people with later stage disease who have this profile, and who received chemotherapy after surgery, and see whether it actually affects survival.

“Chemotherapy can be too harsh for many elderly lung cancer patients, who often have other problems besides cancer. It’s too early to recommend adjuvant chemotherapy for stage I patients until this gene signature is shown to lead to improved treatment in randomised trials,” he said.

In an accompanying comment article in the same issue of the Lancet, Dr Yang Xie and Professor John Minna, from the Southwestern Medical Center in Texas, also called for more research. “Further studies will tell whether the genes in this new assay are of functional relevance and whether they also will provide information on how a lung cancer patient will respond to adjuvant therapy,” they wrote.